Standard Mandarin

| Standard Mandarin | ||

|---|---|---|

| 普通話 / 普通话 Pǔtōnghuà 國語 / 国语 Guóyǔ 華語 / 华语 Huáyǔ 現代標準漢語 / 现代标准汉语 Xiàndài Biāozhǔn Hànyǔ |

||

| Spoken in | ||

| Total speakers | — | |

| Language family | Sino-Tibetan | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | ||

| Regulated by | In the PRC: National Language Regulating Committee[1] In the ROC: National Languages Committee In Singapore: Promote Mandarin Council/Speak Mandarin Campaign[2] |

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | None | |

| ISO 639-2 | ||

| ISO 639-3 | – | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Standard Mandarin, known by various names to native speakers, is the official modern Chinese spoken language used in mainland China and Taiwan, and is one of the four official languages of Singapore.

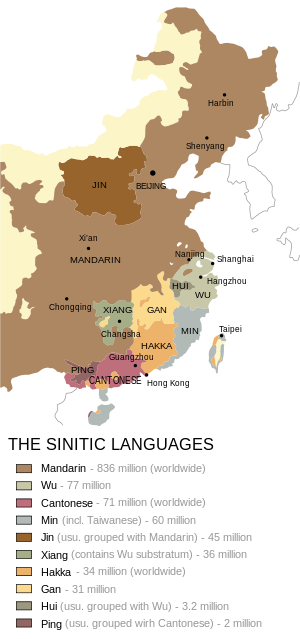

The phonology of Standard Mandarin is based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin, a large and diverse group of Chinese dialects spoken across northern, central and southwestern China. The vocabulary is largely drawn from this group of dialects. The grammar is standardized to the body of modern literary works written in Vernacular Chinese, which in practice follows the same tradition of the Mandarin dialects with some notable exceptions. As a result, Standard Mandarin itself is usually just called "Mandarin" in non-academic, everyday usage. However, linguists use "Mandarin" to refer to the entire language group. This convention is adopted in this article.

Contents |

Names

Standard Mandarin is officially known

- in mainland China, Hong Kong[3] and Macau as Putonghua (simplified Chinese: 普通话; traditional Chinese: 普通話; pinyin: Pǔtōnghuà; literally "common speech").

- in Taiwan as Guoyu, and unofficially in Hong Kong as Gwok Yu (simplified Chinese: 国语; traditional Chinese: 國語; Mandarin Pinyin: Guóyǔ; Jyutping: gwok3 jyu5; literally "national language").

- in Malaysia and Singapore as Huayu (simplified Chinese: 华语; traditional Chinese: 華語; pinyin: Huáyǔ; literally "Chinese (in a cultural sense) language"). In other parts of the world, the three names are used interchangeably to varying degrees, Putonghua being the most common.

Modern Standard Chinese is the most commonly used name for this language by English-speaking linguists, and that name also occurs in Chinese as 現代標準漢語 / 现代标准汉语. The name Guoyu received official recognition in 1909, when the Qing Dynasty determined Standard Mandarin as the "national language". The name Putonghua also has a long, albeit unofficial, pedigree. It was used as early as 1906 in writings by Zhu Wenxiong (朱文熊) to differentiate a modern standard language from classical Chinese and other varieties of Chinese.

For some linguists of the early 20th century, the Putonghua, or "common tongue", was conceptually different from the Guoyu, or "national language". The former was a national prestige dialect or language, while the latter was the legal standard. Based on common understandings of the time, the two were, in fact, different. Guoyu was understood as formal vernacular Chinese, which is close to classical Chinese. By contrast, Putonghua was called "the common speech of the modern man", which is the spoken language adopted as a national lingua franca by conventional usage. The use of the term Putonghua by left-leaning intellectuals such as Qu Qiubai and Lu Xun influenced the People's Republic of China government to adopt that term to describe Standard Mandarin in 1956. Prior to this, the government used both terms interchangeably.[4]

Huayu, or "language of the Chinese nation", originally simply meant "Chinese language", and was used in overseas communities to contrast Chinese dialects against foreign languages. Over time, the desire to standardise the variety of Chinese spoken in these communities led to the adoption of the name "Huayu" to refer to standard Mandarin. This name also avoids choosing a side between the alternative names of Putonghua and Guoyu, which came to have political significance after their usages diverged along political lines between the PRC and the ROC. It also incorporates the notion that Mandarin is usually not the national or common language of the areas in which overseas Chinese live.

History

Chinese languages have always had dialects; hence prestige dialects have always existed, and linguae francae have always been needed. Confucius, for example, used yǎyán (雅言), or "elegant speech", rather than colloquial regional dialects; text during the Han Dynasty also referred to tōngyǔ (通语), or "common language". Rime books, which were written since the Southern and Northern Dynasties, may also have reflected one or more systems of standard pronunciation during those times. However, all of these standard dialects were probably unknown outside the educated elite; even among the elite, pronunciations may have been very different, as the unifying factor of all Chinese dialects, Classical Chinese, was a written standard, not a spoken one.

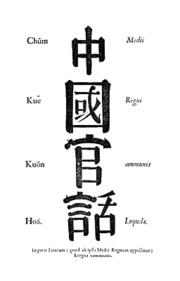

The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) and the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) began to use the term guānhuà (官话/官話), or "official speech", to refer to the speech used at the courts. The term "Mandarin" comes directly from the Portuguese. The word mandarim was first used to name the Chinese bureaucratic officials (i.e., the mandarins), because the Portuguese, under the misapprehension that the Sanskrit word (mantri or mentri) that was used throughout Asia to denote "an official" had some connection with the Portuguese word mandar (to order somebody to do something), and having observed that these officials all "issued orders", chose to call them mandarins. The use of the word mandarin by the Portuguese for the Chinese officials, as well as its putative connection with the Portuguese verb mandar is attested already in De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu (1617) by Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault.[6]

From this, the Portuguese immediately started calling the special language that these officials spoke amongst themselves (i.e., "Guanhua") "the language of the mandarins", "the mandarin language" or, simply, "Mandarin". The fact that Guanhua was, to a certain extent, an artificial language, based upon a set of conventions (that is, the various Mandarin dialects for grammar and meaning, and the specific dialect of the Imperial Court's locale for its pronunciation), is precisely what makes it such an appropriate term for Modern Standard Chinese (also the various Mandarin dialects for grammar and meaning, and their dialect of Beijing for its pronunciation).

It seems that during the early part of this period, the standard was based on the Nanjing dialect of Mandarin, but later the Beijing dialect became increasingly influential, despite the mix of officials and commoners speaking various dialects in the capital, Beijing. In the 17th century, the Empire had set up Orthoepy Academies (正音书院/正音書院 Zhèngyīn Shūyuàn) in an attempt to make pronunciation conform to the Beijing standard. But these attempts had little success since as late as the 19th century the emperor had difficulty understanding some of his own ministers in court, who did not always try to follow any standard pronunciation. Although by some account, as late as the early 20th century, the position of Nanjing Mandarin was considered to be higher than that of Beijing by some and the Chinese Postal Map Romanization standards set in 1906 included spellings with elements of Nanjing pronunciation.[7] Nevertheless, by 1909, the dying Qing Dynasty had established the Beijing dialect as guóyǔ (国语/國語), or the "national language".

After the Republic of China was established in 1912, there was more success in promoting a common national language. A Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation was convened with delegates from the entire country, who were chosen as often due to political considerations as they were for their linguistic expertise. A Dictionary of National Pronunciation (国音字典/國音字典) was published, which was based on the Beijing dialect. Meanwhile colloquial literature continued to develop apace vernacular Chinese, despite the lack of a standardized pronunciation. Gradually, the members of the National Language Commission came to settle upon the Beijing dialect, which became the major source of standard national pronunciation due to the prestigious status of that dialect. In 1932, the commission published the Vocabulary of National Pronunciation for Everyday Use (国音常用. 字汇/字國音常用. 字彙), with little fanfare or official pronunciation. This dictionary was similar to the previous published one except that it normalized the pronunciations for all characters into the pronunciation of the Beijing dialect. Elements from other dialects continue to exist in the standard language, but as exceptions rather than the rule.[8]

The People's Republic of China, established in 1949, continued the effort. In 1955, the name guóyǔ was replaced by pǔtōnghuà (普通话/普通话), or "common speech". (By contrast, the name guóyǔ continued to be used by the Republic of China which, after the 1949 loss in the Chinese Civil War, had a territory consisting of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu Islands, and smaller islands.) Since then, the standards used in mainland China and Taiwan have diverged somewhat, especially in newer vocabulary terms, and a little in pronunciation.

The advent of the 20th century has seen many profound changes in Standard Mandarin. Many formal, polite and humble words that were in use in imperial China have not been used in daily conversation in modern-day Standard Mandarin, such as jiàn (贱/賤 "my humble") and guì (贵/貴 "your honorable").

The word 'Putonghua' was defined in October 1955 by the Minister of Education Department in mainland China as follows: "Putonghua is the common spoken language of the modern Han group, the lingua franca of all ethnic groups in the country. The standard pronunciation of Putonghua is based on the Beijing dialect, Putonghua is based on the Northern dialects [i.e. the Mandarin dialects], and the grammar policy is modeled after the vernacular used in modern Chinese literary classics." [9]

In both mainland China and Taiwan, the use of Standard Mandarin as the medium of instruction in the educational system and in the media has contributed to the spread of Standard Mandarin. As a result, Standard Mandarin is now spoken fluently by most people in mainland China and Taiwan.

In Hong Kong and Macau, which are now special administrative regions of the People's Republic of China, Standard Cantonese has been the primary language spoken by the majority of the population, due to historical and linguistic reasons. After Hong Kong's handover from Britain and Macau's handover from Portugal, Standard Mandarin has become only slightly more understood (but still not widely spoken) and is used by the governments of the two territories to communicate with the Central People's Government of the PRC. Cantonese remains the official government language of Hong Kong and Macau when not communicating with mainland China.

Phonology

The Standard Mandarin phoneme inventory consists of about two dozen consonants, of which only /n/, /ŋ/, and under certain circumstances /ɻ/ can occur in the syllable coda; about half a dozen vowels, many of which form diphthongs and triphthongs; and four tones. Statistically, vowels and tones are of similar importance in Standard Mandarin.[10]

Standard Mandarin and Beijing dialect

Due to evolution and standardization, Standard Mandarin, although based on the Beijing dialect, is no longer synonymous with it. Part of this was due to the standardization of Mandarin to reflect a greater vocabulary scheme and a more archaic and "proper-sounding" pronunciation and vocabulary. The areas near Beijing, especially the cities of Chengde and Shijiazhuang in neighbouring Hebei province, speak a form of Mandarin closest to its fully standardized pronunciation; this form is generally heard on national and local television and radio.

By the official definition of the People's Republic of China, Standard Mandarin uses:

- The phonology or sound system of Beijing. A distinction should be made between the sound system of a dialect or language and the actual pronunciation of words in it. The pronunciations of words chosen for Standard Mandarin—a standardized speech—do not necessarily reproduce all of those of the Beijing dialect. The pronunciation of words is a standardization choice and occasional standardization differences (not accents) do exist, between Putonghua and Guoyu, for example.

- In fluent speech, Chinese speakers can easily tell the difference between a speaker of the Beijing dialect and a speaker of Standard Mandarin. Beijingers speak Standard Mandarin with elements of their own dialect in the same way as other speakers.

- The vocabulary of Mandarin dialects in general. This means that all slang and other elements deemed "regionalisms" are excluded. On the one hand, the vocabulary of all Chinese dialects, especially in more technical fields like science, law, and government, are very similar. (This is similar to the profusion of Latin and Greek words in European languages.) This means that much of the vocabulary of standardized Mandarin is shared with all varieties of Chinese. On the other hand, much of the colloquial vocabulary and slang found in Beijing dialect is not found in Standard Mandarin, and may not be understood by people outside Beijing.

- The grammar and usage of exemplary modern Chinese literature, such as the work of Lu Xun, collectively known as "Vernacular Chinese" (baihua). Vernacular Chinese, the standard written form of modern Chinese, is in turn based loosely upon a mixture of northern (predominant), southern, and classical grammar and usage. This gives formal standard Mandarin structure a slightly different feel from that of street Beijing dialect.

In theory the Republic of China in Taiwan defines standard Mandarin differently, though in reality the differences are minor and are concentrated mostly in the tones of a small minority of words.

Speakers of Standard Mandarin generally have little difficulty understanding the Beijing accent, which the former is based on. Natives of Beijing commonly add a final "er" (/ɻ/) (兒音/儿音; pinyin: éryīn) — commonly used as a diminutive — to vocabulary items, as well as use more neutral tones in their speech. An example of Standard Mandarin versus the Beijing dialect would be: standard men (door) compared with Beijing menr. These give the Beijing dialect a somewhat distinctive lilt compared to Standard Mandarin spoken elsewhere. The dialect is also known for its rich colloquialisms and idiomatic expressions.

Although Chinese speakers make a clear distinction between Standard Mandarin and the Beijing dialect, there are aspects of Beijing dialect that have made it into the official standard. Standard Mandarin has a T-V distinction between the polite and informal versions of you that comes from Beijing dialect, but its use is quite diminished in daily speech. In addition, it also distinguishes between "zánmen" (we including the listener) and "wǒmen" (we not including the listener). In practice, neither distinction is commonly used by most Chinese, at least outside the Beijing area.

The following samples are some phrases from Beijing dialect which are not yet accepted into Standard Mandarin:

- 倍儿: bèir means 'very much'; 拌蒜: bàn suàn means 'stagger'; 不吝: bù lìn means 'do not worry about'; 撮: cuō means 'eat'; 出溜: chū liū means 'slip'; (大)老爷儿们儿: dà lǎo yer menr means 'man, male';

The following samples are some phrases from Beijing dialect which have been already accepted as Standard Mandarin:

- 二把刀: èr bǎ dāo means 'not very skillful'; 哥们儿: gē ménr means 'good male friend(s)', 'buddy(ies)'; 抠门儿: kōu ménr means 'parsimous' or 'stingy'.

Standard Mandarin and other dialects and languages

Although Standard Mandarin is now firmly established as the lingua franca in Mainland China, the national standard can be somewhat different from the other dialects in the vast Mandarin dialect chain, to the point of being to some extent unintelligible. However, pronunciation differences within the Mandarin dialects are usually regular, usually differing only in the tones. For example, the character for "sky" 天 is pronounced with the first tone in the Beijing dialect and in Standard Mandarin (pinyin: tiān, tian1),[11] but is the falling tone in the Tianjin dialect of Mandarin.

Although both Mainland China and Taiwan use Standard Mandarin in the official context and are keen to promote its use as a national lingua franca, there is no official intent to have Standard Mandarin replace the regional languages. As a practical matter, speaking only Standard Mandarin in areas such as in southern China or Taiwan can be a social handicap, as some elderly or rural Chinese-language speakers do not speak Standard Mandarin fluently (although most do understand it). In addition, it is very common for it to be spoken with the speaker's regional accent, depending on factors as age, level of education, and the need and frequency to speak correctly for official or formal purposes. This situation appears to be changing, though, in large urban centers, as social changes, migrations, and urbanization take place.

In the predominantly Han areas in Mainland China, while the use of Standard Mandarin is encouraged as the common working language, the PRC has been sensitive to the status of minority languages and has not discouraged their use. Standard Mandarin is very commonly used for logistical reasons, as in many parts of southern China the linguistic diversity is so large that neighboring city dwellers may have difficulties communicating with each other without a lingua franca.

In Taiwan, the relationship between Standard Mandarin and other languages in Taiwan, particularly Taiwanese Hokkien, has been more heated politically. During the martial law period under the Kuomintang (KMT) between 1949 and 1987, the KMT government discouraged or, in some cases, forbade the use of Taiwanese Minnan and other vernaculars. This produced a political backlash in the 1990s. Under the administration of Chen Shui-Bian, other Taiwanese languages were taught as an individual class, with dedicated textbooks and course materials. The former President, Chen Shui-Bian, often spoke in Taiwanese Minnan during speeches, while after late 1990s, former President Lee Teng-hui, also speaks Taiwanese Minnan openly.

In Singapore, the government has heavily promoted a "Speak Mandarin Campaign" since the late 1970s. The use of other Chinese languages in broadcast media is prohibited and their use in any context is officially discouraged. This has led to some resentment amongst the older generations, as Singapore's migrant Chinese community is made up almost entirely of south Chinese descent. Lee Kuan Yew, the initiator of the campaign, admitted that to most Chinese Singaporeans, Mandarin was a "stepmother tongue" rather than a true mother language. Nevertheless, he saw the need for a unified language among the Chinese community not biased in favor of any existing group.[12]

See also:

- Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation

- Mandarin Promotion Council

- Speak Mandarin Campaign

Accents

Most Chinese (Beijingers included) speak Standard Mandarin with elements of their own dialects (i.e. their "accents") mixed in.

For example, natives of Beijing, add a final "er" (/ɻ/) — commonly used as a diminutive — sound to vocabulary items that other speakers would leave unadorned (兒音/儿音; pinyin: éryīn).

On the other hand, speakers from northeastern and southern China as well as Taiwan often mix up zh and z, ch and c, and sh and s because their own home dialects often do not include retroflex initial consonants. Speakers of various Chinese dialects do not distinguish initial n and l, or final n and ng. As a result, it can be difficult for people who do not have the standard pronunciation to use pinyin for dictionary look-up or typing on a computer, because they do not distinguish these sounds.

See List of Chinese dialects for a list of articles on individual dialects of Chinese languages and how their features differ from Standard Mandarin.

Role of standard Mandarin

From an official point of view, Standard Mandarin serves the purpose of a lingua franca — a way for speakers of the several mutually unintelligible Han Chinese languages, as well as the Han and Chinese minorities, to communicate with each other. The very name Putonghua, or "common speech," reinforces this idea. In practice, however, due to Standard Mandarin being a "public" lingua franca, other languages or dialects, both Han and non-Han, have shown signs of losing ground to Standard Mandarin, to the chagrin of certain local culture proponents.

On Taiwan, Guoyu (national language) continues to be the official term for standard Mandarin. The term Guoyu is relatively rarely used in Mainland China, because declaring a Beijing-dialect-based standard to be the national language would be deemed unfair to other Chinese dialects and ethnic minorities. The term Putonghua (common speech), on the contrary, implies nothing more than the notion of a lingua franca. However, the term Guoyu does persist among many older Mainland Chinese, and it is common in U.S. Chinese communities, even among Mainlanders. Some in Taiwan, especially proponents of Taiwan independence, also object to the term Guoyu to refer to standardized Mandarin, on the grounds that the "nation" referred to in the name of the language is China and that Taiwan is or should be independent. They prefer to refer to Mandarin with the terms "Beijing dialect" or Zhongwen (writing of China). Those hold other positions on the political spectrum in Taiwan display different views.

In December 2004, the first survey of language use in the People's Republic of China revealed that only 53% of its population, about 700 million people, could communicate in Standard Mandarin. (China Daily) A survey by South China Morning Post released in September 2006 gave the same result. This 53% is defined as a passing grade above 3-B (i.e. error rate lower than 40%) of the Evaluation Exam. Another survey in 2003 by the China National Language And Character Working Committee (国家语言文字工作委员会) shows, if mastery of Standard Mandarin is defined as Grade 1-A (an error rate lower than 3%), the percentages were as follows: Beijing 90%, Shanghai 3%, Tianjin 25%, Guangzhou 0.5%, Dalian 10%, Xi'an 12%, Chengdu 1%, Nanjing 2%.

With the fast development of China, more Chinese people leaving rural areas for cities for job or study opportunities, and the Mandarin Level Evaluation Exam (普通话水平测试) has quickly become popular. Most university graduates take this exam before looking for a job. Many companies require a basic Mandarin Level Evaluation Certificate from their applicants, barring applicants who were born or bred in Beijing, since their Proficiency level is believed to be inherently 1-A (一级甲等)(Error rate: lower than 3%). As for the rest, the score of 1-A is rare. People who get 1-B (Error rate: lower than 8%) are considered qualified to work as television correspondents or in broadcasting stations. 2-A (Error rate: lower than 13%) can work as Chinese Literature Course teachers in public schools. Other levels include: 2-B (Error rate: lower than 20%), 3-A (Error rate: lower than 30%) and 3-B (Error rate: lower than 40%). In China, a proficiency of level 3-B usually cannot be achieved unless special training is received. Even if many Chinese do not speak Standard Mandarin with standard pronunciation, spoken Standard Mandarin is widely understood to some degree.

The China National Language And Character Working Committee was founded in 1985. One of its important responsibilities is to promote Standard Mandarin and Mandarin Level proficiency for Chinese native speakers. (Its website link can be found in the external links section.)

Common Phrases

| English | Chinese (Traditional) |

Chinese (Simplified) |

Pinyin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hello! | 你好! | 你好! | Nǐ hǎo! |

| What is your name? | 你叫甚麼名字? | 你叫什么名字? | Nǐ jiào shénme míngzi? |

| My name is... | 我名字叫... | 我名字叫... | Wǒ míngzi jiào ... |

| How are you? | 你好嗎?/ 你怎麼樣? | 你好吗?/ 你怎么样? | Nǐ hǎo ma? / Nǐ zěnmeyàng? |

| I am fine, how about you? | 我很好,你呢? | 我很好,你呢? | Wǒ hěn hǎo, nǐ ne? |

| I don't want it / I don't want to | 我不要。 | 我不要。 | Wǒ bú yào. |

| Thank you! | 謝謝! | 谢谢! | Xièxiè |

| Welcome! / You're welcome! (Literally: No need to thank me!) / Don't mention it! (Literally: Don't be so polite!) | 歡迎!/ 不用謝!/ 不客氣! | 欢迎!/ 不用谢!/ 不客气! | Huānyíng! / Búyòng xiè! / Bú kèqì! |

| Yes. / Correct. | 是。 / 對。 | 是。 / 对。 | Shì. / Duì. |

| No. / Incorrect. | 不。/ 不對。 | 不。/ 不对。 | Bù. / Bú duì. |

| When? | 甚麼時候? | 什么时候? | Shénme shíhou? |

| How much money? | 多少錢? | 多少钱? | Duōshǎo qián? |

| How long is it? (in terms of length) | 多長? | 多长? | Duō cháng? |

| Can you speak a little slower? | 您能說得再慢些嗎? | 您能说得再慢些吗? | Nín néng shuō de zài mànxiē ma? |

| Good morning! / Good morning! | 早上好! / 早安! | 早上好! / 早安! | Zǎoshang hǎo! / Zǎo'ān! |

| Goodbye! | 再見! | 再见! | Zàijiàn! |

| How do you get to the airport? | 去機場怎麼走? | 去机场怎么走? | Qù jīchǎng zěnme zǒu? |

| I want to fly to London on the eighteenth | 我想18號坐飛機到倫敦 | 我想18号坐飞机到伦敦 | Wǒ xiǎng shíbā hào zuò fēijī dào Lúndūn. |

| How much will it cost to get to Munich? | 到慕尼黑需要多少錢? | 到慕尼黑需要多少钱? | Dào Mùníhēi xūyào duōshǎo qián? |

| I don't speak Chinese very well. | 我的中文講得不太好. | 我的中文讲得不太好. | Wǒ de Zhōngwén jiǎng de bú tài hǎo. |

| New | 新 | 新 | Xīn |

See also

- Mandarin Chinese

- Beijing dialect

- History of Standard Mandarin

- Chinese grammar

- Mandarin slang

- Chinese speech synthesis

- Taiwanese Mandarin

- Singaporean Mandarin

- Malaysian Mandarin

Notes

- ↑ http://www.china-language.gov.cn/ (Chinese)

- ↑ http://www.mandarin.org.sg/2009/

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Yuan, Zhongrui. (2008) "国语、普通话、华语 (Guoyu, Putonghua, Huayu)". China Language National Language Committee, People's Republic of China

- ↑ FOURMONT, Etienne. Linguae Sinarum Mandarinicae hieroglyphicae grammatica duplex, latinè, & cum characteribus Sinensium. Item Sinicorum Regiae Bibliothecae librorum catalogus...

- ↑ Page 45 in the English translation, "China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matteo Ricci", Random House, New York, 1953. In the original Latin, vol. 1, p. 51: "Lusitani Magistratus illos, à mandando fortasse, Mandarinos vocant, quo nomine iam etiam apud Europæos Sinici Magistratus intelliguntur".

- ↑ From Louis Richard. L. Richard's comprehensive geography of the Chinese empire and dependencies. Translated into English, revised and enlarged by M. Kennelly, S.J. [Translation of "Geographie de l'empire de Chine," Shanghai, 1905.] Shanghai: T'usewei Press, 1908. p. iv.)

- ↑ Title:The languages of China, Author:S. Robert Ramsey, Publisher:Princeton University Press, 1987, ISBN 0691066949, 9780691066943, chapter 1.

- ↑ Original text in Chinese: "普通话就是现代汉民族共同语,是全国各民族通用的语言。普通话以北京语音为标准音,以北方话为基础方言,以典范的现代白话文著作为语法规范"

- ↑ Surendran and Levow, The functional load of tone in Mandarin is as high as that of vowels, Proceedings of Speech Prosody 2004, Nara, Japan, pp. 99-102.

- ↑ Dr. Timothy Uy and Jim Hsia (ed.), Webster's Digital Chinese Dictionary, Loqu8 Press, 2009. WDCD - Advanced Reference Edition

- ↑ Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story: 1965-2000, HarperCollins, 2000. ISBN 0-06-019776-5.

References

- Branner, David Prager (ed.) (2006). The Chinese Rime Tables: Linguistic Philosophy and Historical-Comparative Phonology. Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science, Series IV: Current Issues in Linguistic Theory; 271. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. ISBN 90-272-4785-4.

- Chao, Y.R., A Grammar of Spoken Chinese, University of California Press, (Berkeley), 1968.

- Chen, Ping (1999). Modern Chinese: History and sociolinguistics. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521645727.

- Hsia, T., China’s Language Reforms, Far Eastern Publications, Yale University, (New Haven), 1956.

- Ladefoged, Peter; & Maddieson, Ian. (1996). The sounds of the world's languages. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-19814-8 (hbk); ISBN 0-631-19815-6 (pbk).

- Ladefoged, Peter; & Wu, Zhongji. (1984). Places of articulation: An investigation of Pekingese fricatives and affricates. Journal of Phonetics, 12, 267-278.

- Lehmann, W.P. (ed.), Language & Linguistics in the People’s Republic of China, University of Texas Press, (Austin), 1975.

- Lin, Y., Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1972.

- Milsky, C., "New Developments in Language Reform", The China Quarterly, No.53, (January-March 1973), pp. 98–133.

- Norman, J., Chinese, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1988.

- Ramsey, R.S.(1987). The Languages of China. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01468-X

- San Duanmu (2000) The Phonology of Standard Chinese ISBN 0-19-824120-8

- Seybolt, P.J. & Chiang, G.K. (eds.), Language Reform in China: Documents and Commentary, M.E. Sharpe, (White Plains), 1979.

- Simon, W., A Beginners' Chinese-English Dictionary Of The National Language (Gwoyeu): Fourth Revised Edition, Lund Humphries, (London), 1975.

External links

- General Introduction to Chinese Language

- Learning Chinese Language in BBC

- Webster's Digital Chinese Dictionary Contemporary Chinese-English dictionary with 84,000 entries. Pinyin Starter edition is free.

- Popup Chinese - online mp3 podcasts and lessons in standard mandarin. Also accompanying videos, character-writing tools, and hsk test prep materials.

- Learn Chinese by annotation - free online tool for the use of segmenting Chinese text and give each word its definition,pinyin,examples and so forth.

- Mandarin module - Online vocabulary memorization system

- Arch Chinese - Learn To Read And Write Chinese Characters - Online Chinese character stroke order animations for over 12,000 frequently used Chinese characters, simplified and traditional, with native speaker pronunciations, example phrases, writing worksheet generation and character learning flashcards.

- Chinese / English / French online characters Dictionary - Online MandarinChinese/English/French characters Dictionary, Chinese tons, Chinese characters, Chinese Exercises

- Standard Mandarin Pinyin Table The complete listing of all Pinyin syllables used in standard Mandarin, along with native speaker pronunciation for each syllable.

- Stroke order for Chinese character Official website of Taiwan's Ministry of Education

- Introductory Course for Mandarin Chinese

- New Asia Yale-in-China Chinese Language Center of the Chinese University of Hong Kong

- The musical nature of the Four Tones of Chinese mandarin

- Elementary Online Textbook for Mandarin Chinese

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||